“If we want to change the world in a way that will solve climate, and if we want to reduce our carbon footprint, it’s not about us. It’s about changing the system.” — Auden Schendler

What does it take to drive meaningful systems change in the face of the climate crisis? Auden Schendler, VP of Sustainability at Aspen Skiing Company, knows that it requires bold, impactful action that goes far beyond token sustainability measures. In his presentation for Destination Think’s 24 Hours of Travel Innovation event on World Tourism Day 2024, he challenged the travel industry to rethink its approach to sustainability and embrace transformative solutions.

Auden drew a clear distinction between superficial efforts, like changing lightbulbs, and systemic change that addresses the root causes of the climate crisis. He argued that the environmental movement, and much of corporate sustainability, has been “complicit with the fossil fuel economy,” often avoiding actions that would disrupt it.

He shared inspiring examples of what meaningful change looks like. In one instance, Aspen Skiing Company helped transition their coal-reliant utility to 80% renewable energy. They accomplished this through advocacy, community organizing, and persistent corporate influence. In addition to making small operational improvements, the company leveraged its power to push for significant policy shifts.

Auden emphasized that businesses, particularly in the travel industry, have both a responsibility and an opportunity to lead. The industry’s unique ability to forge emotional connections with people makes it especially powerful. By advocating for climate policies and engaging customers with meaningful climate messaging, companies can leverage their influence to inspire action and drive real progress.

His message is clear: the travel industry isn’t just a bystander in the climate conversation—it holds the potential to solve civilizational challenges, especially when working as a collective.

You’ll also learn:

- Why business-as-usual forms of sustainability aren’t enough, and why the travel industry been stuck there.

- About the civilizational challenge that lies ahead.

- How you can help the travel industry lead systemic change.

- The meaning of eudaimonia and human thriving.

- About Auden’s new book, Terrible Beauty: Reckoning with Climate Complicity and Rediscovering Our Soul.

Subscribe to Travel Beyond through Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast player.

Show notes

Aspen Skiing Company — A ski resort operator based in Aspen, Colorado, renowned for its commitment to sustainability and environmental advocacy in the tourism industry.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) — The U.S. government agency focused on understanding and managing the Earth’s oceans, atmosphere, and coastal ecosystems through research, conservation, and climate monitoring.

Protect Our Winters (POW) — A nonprofit organization that mobilizes the outdoor sports community to advocate for policies and actions addressing climate change and promoting environmental sustainability.

Yale Program on Climate Communication — A research organization that studies and advances public understanding and engagement with climate change through effective communication strategies and outreach initiatives.

Episode transcript

This transcript was generated using AI and has been lightly reviewed for accuracy.

Auden Schendler: History is replete with people, uh, examples of citizens who have no power at all and drove disproportionate change. And the tourism industry is one of the most powerful because people love you and you are the thing that they love in the world. We can use that. The things we love as a propulsion, as power for solving the problem, the threat to all of those things.

So, it’s the greatest opportunity ever presented to civilization.

David Archer: Welcome back to Travel Beyond, where we partner with leading destinations to bring you inspiring solutions to the greatest challenges facing communities and the planet. I’m David Archer from Destination Think, and I’m recording from Haida Gwaii, the territory of the Haida Nation off the north coast of British Columbia in Canada.

On this show we look at the role of travel and choose to highlight destinations that are global leaders. We talk to the changemakers who are addressing regenerative travel through action in their communities and often from the bottom up. And we’re actively sharing and looking for the best examples of efforts to regenerate economies, communities, and ecosystems.

If you have a story like that to share you can reach me at david at destinationthink.com. And I’d also recommend checking out a Destination Think project called 100 Travel Innovations for some examples of what I’m talking about. These are bite sized stories of solutions led by the travel industry, and you can find those at innovate.destinationthink.com. Well, it’s hard to believe, but this is our final episode for 2024. And to cap off the year, we’re sharing a presentation that was produced for one of our most momentous times of the year, I would say, which is World Tourism Day. So back in September, this talk was part of our 24 Hours of Travel Innovation event.

And we’d like to resurface it because Auden Schendler has been an inspiration to all of us at Destination Think. You’ll remember him from previous episodes, starting all the way back in our Aspen season. Auden is the Senior Vice President of Sustainability at Aspen Skiing Company, which operates four ski areas and is a major player in the local tourism industry.

And Auden’s work has resulted in some of the most inspiring solutions from travel that we’ve so far. And so just to choose one of those, he and Aspen Skiing Company advocated successfully to change the electricity source powering the ski hills so that today they use mostly renewable energy instead of coal.

So, you know, talk about going beyond changing light bulbs. Examples like these go past individual actions and start to make the systemic changes that will have the biggest impact on issues like the climate crisis. And in this talk, we’re encouraged to call upon the enormous resources and potential influence that the travel industry holds as a collective.

One more note is that since this conversation took place, Auden has released his new book called Terrible Beauty, Reckoning with Climate Complicity and Rediscovering Our Soul. And that is now available to order or maybe to pick up from your favorite local bookshop. So let’s go onward to Auden Schendler’s presentation about systemic change and a Q& A with Rodney Payne.

First, to introduce the talk, we’ll hear a few words from Hadley Dryden, the general manager of Destination Hauraki Coromandel in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Hadley Dryden: Welcome everyone to the World Tourism Day. 24 hours of travel innovation. Kia ora, my name’s Hadley Dryden, General Manager of Destination Hauraki Coromandel, here in Aotearoa, New Zealand. It’s my pleasure to introduce this session topic, Influencing Systemic Change with Auden Schindler. Senior Vice President Sustainability at Aspen One, and Rodney Payne of Destination Think, who we’ll hear from shortly.

Influencing systemic change in tourism requires rethinking traditional models, fostering collaboration across sectors, and embedding values that prioritise the wellbeing of communities, the environment, and economies. This conversation explores how the industry can drive meaningful change, embracing innovative approaches that makes tourism a force for good globally.

Here in Hauraki Coromandel, locals and visitors enjoy a beautiful region where green pastures meet a rugged peninsula surrounded by 400 kilometers of coastline. with a small population that enjoy a laid back lifestyle. It is essential that we take proactive steps to ensure tourism protects this unique lifestyle and the natural environment.

Sustainable innovations are especially important to our region because they help protect our unique natural landscapes, support the well being of our communities, and preserve this region for the next generation of locals and visitors. Recently, we led a sustainability program involving over 60 businesses across the region.

Each participant received a carbon and waste assessment, with personalized recommendations to enhance their environmental practices. Building on this momentum, Destination Hauraki Coromandel has expanded the program to include biodiversity as well. In collaboration with the local Indigenous Nursery, in the Predator Free Hauraki Coromandel Community Trust, we are introducing a donation platform that enables businesses, locals and visitors to contribute to tree planting and conservation efforts.

By working together, this platform offers tangible actions to support the region’s good for your soul brand and protect today so that we can visit a better tomorrow. Without further ado, I’ll pass you over to hear from Auden Schindler and Rodney Payne. To share their points for influencing systemic change.

Kia ora and thank you.

Rodney Payne: Hello everybody. My name is Rodney Payne. I’m the CEO of Destination Think and I’m here with Auden Schendler, the Senior Vice President of Sustainability at Aspen Skiing Company in Colorado. Auden, welcome. I’m excited to have you here today because your work has been an inspiration for many travel destinations and businesses and organizations like ours.

In influencing systems change, which is what we’re here to talk about. You’ve also, you’ve also been a guest on our podcast and I look forward to sort of expanding on that and, and, uh, and diving a bit deeper today. So I’m, we’re going to start this, this is a two part session. Uh, we’re going to begin, um, with, with you, Aud and giving a presentation, and then we’re going to come back and have a bit of a discussion towards the end.

So. I’m going to start by handing over to you to share some of your experience, what you’ve learned and, and some of your sort of insights and advice and, uh, about the, the truly incredible book that you’re, uh, about to be releasing. So I’ll, I’ll drop off for a second here and over to you.

Auden Schendler: Okay. Great, Rodney. Thanks a lot. And I’m going to be talking about. What it means to address the climate problem at scale in a meaningful way versus a token way and part of the way we can do that. The motivation for doing that is why we should care. So I want to show you a video of my son Elias when he was about eight.

Uh, chopping wood in the backyard. Take a look at this and watch his face. See that expression? The look on his face when he cleaves that, um, round of wood pretty well. Not perfectly well. Doesn’t cut his foot off. Doesn’t, uh, chop the hose. That’s the look you’ve seen when your kids first rode a carousel.

It’s the look you’ve seen when they first tried frosted flakes. This is a thriving person. He’s in a landscape, a stable landscape in the mountains. Doing something that has been passed on for generations. Chopping wood is something you learn from your parents. The axe he’s holding, which I put a new handle on was his great grandfather’s axe, so that’s probably 150 years old.

And Aristotle had a term for this. It’s eudaimonia, which basically means human thriving. And the problem with ensuring that all humans thrive, regardless of what your thriving means, it could be happy subsistence, it could be a successful tourism economy, it could be whatever, is that when you look into the future, this is a map developed by NOAA, American um, institution, showing what soil moisture content looks like in 2090.

And the dark colors are soil moisture content equivalent to the dust bowl. So you can see Colorado, it’s about center left on this map. That’s where Elias is going to be when he’s what he used to call an old little man. And there’s a dissonance in thinking about this. You have this beauty of the world and this incredible thriving boy who’s sort of representative of thriving in the world.

And Bob Dylan put it right in a song, tomorrow’s a long time. He said, I can’t hear the echoes of my footsteps or remember the sound of my own name. And what he meant by that was this feeling of disassociation and of alienation from the world because what you’re dealing with is what I call terrible beauty, the stunning beauty of the world and family and things you love overlaid with the fact that this is all threatened by climate change, and you don’t need to look far into the newspapers to see what I’m talking about.

This is a flood in Germany, but it could be anywhere if you just Google floods global. And of course, these are increasing due to a warmer climate that has more energy and can store more water. But the point here is that you can’t thrive if you’re constantly dealing with mud and something, your basement and repairing infrastructure and so forth.

I mean, look at this, this’ll take years to recover from. And the things that make us great as humans. are the things we do when we don’t have to worry about pure survival. And I realized that not everyone gets to enjoy a baseball game. This is Nolan Arenado, who used to play for the Colorado Rockies. He’s a great third baseman.

But every human deserves a shot at this level of joy and thriving regardless of their wealth. And that should be the vision that we have for humanity, not just for our own countries or places. Emmylou Harris, an American singer, just an amazing, wonderful example of thriving human society that’s able to pursue art and culture and poetry and song and not just rebuild after the last disaster.

Kevin Anderson is a climatologist. He used to run the Tyndall Center in the UK. And he was talking about where we’re headed from a warming perspective. And basically we’re sort of gone past two degrees Celsius. We’re more likely headed toward three or four C warming above pre industrial times by 2100.

Kevin Anderson, he’s a scientist. So he’s, he speaks in kind of nerd speak, but he said four degrees Celsius. is incompatible with a global organized society. And what does that mean? I mean, come on, give us, give us something comprehensible. Well, this is what it means. It’s Mad Max. This is an anarchic society that could have come about as a result of drought or flood or fire or things like climate change.

And so this is the kind of thing we’re trying to avoid when we work on climate change. NASA has an incredible site. where you can look up the latest month or the latest year and find the temperature anomaly. I did this for April. Just as an example, as you know, 2023 was the hottest year in the recorded temperature record.

But look at this. The scale on the bottom is degrees Celsius. So we’re looking at a different planet that is warming in a way that is most damaging because the Arctic you can see, which is white, is melting and becoming dark. And the northern forests are heating up and burning and releasing carbon. And there’s also methane up there.

Remember that human civilization evolved in a 12, 000 year period in which temperature toggled very little. It didn’t toggle 6. 2 degrees Celsius, which you could call about 12 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s, it’s an insane thing. So in such a world, Elias doesn’t get to collect gnomes. Your family doesn’t get to play around with ski helmets on the couch.

You don’t get to hang out, relaxing, wearing the “Oh, Gnome, You Didn’t” t shirt. You don’t get to serve your young children champagne even though it’s illegal and they’re too young. Gnomes are a big theme. We can talk about that at the bar. You don’t get to dress up like a gnome on the Grand Canyon by the fire.

Or put your tuxedo on and dress like the Joker for Halloween. Or use the same tuxedo to fish in the Gunnison Gorge while drinking a Manhattan. Or stand in a shaft of light in the desert. This is a picture of my hometown taken by my friend Pete McBride, who’s a photographer of seven D. C. 10 dropping slurry right above my house.

This is a threat not just to obviously our economies, but to the things that make us great as human beings, our town didn’t burn down, but it almost burned down. And here’s what saved us 40 million in airdrops that were paid for by American taxpayers. And that was money we’ll never see again. It was thrown down the drain.

And if we hadn’t lived in a warming world and we didn’t have to worry about these sorts of threats over and over again, you could spend that money on whatever you want. Education, art, culture, social services, housing, pick the thing. In the face of catastrophic climate change already happening and in our faces and causing catastrophe every year, what does corporate America do?

Corporate America, and this is my work. They change light bulbs, which manifestly isn’t enough to solve the problem. They reduce their carbon footprint, which doesn’t really make sense as a global climate solution, because it’s just you. And it’s really hard to do, and it’s not national or international. So in my career, I worked in this field of CSR ESG, corporate social responsibility, environmental and social governance.

And I was riding my bike one day in the mountains and I thought, let me think about this. I’m going to do a thought experiment. I’m going to do a list of all the things that best practice in my field would suggest you do. Things like reporting on your impact, carbon footprint reduction, carbon targets, third party certifications, measurement, dashboard.

And then I thought, what if the fossil fuel industry were to make a list of things that it would ask corporations to do to appear to be environmental, but to not get in the way of monetizing the proven reserves of fossil fuels in the world. Here’s a hint. Same list. So the idea that popped into my head on this bike ride was the concept of complicity.

And what I realized is that the environmental movement, but in particular, the corporate sustainability movement has been complicit. With a fossil fuel economy and essentially does nothing that would get in the way of that economy. Okay So a good question would be what might get in the way of those things?

And here’s a list of what I call dangerous meaningful actions; Pressuring trade groups in your industry saying you have to be more vocal on climate, you have to advocate more, you have to educate us. You have to bring in speakers, public statements from powerful people saying we need government policy on this.

Calling peer businesses to account, that’s not easy to do. Honesty, instead of saying we’re doing great when you know we’re not. And you can see the list, but this is a, the kinds of things that involve a concept you might call power wielding, instead of dinking around with token ideas. So this was the idea.

That I came up with and sort of an epiphany and a realization that we have to think differently. But the first question was, why are we stuck in the box? And the short answer is, is that in the United States at least, but this has been a global effort, the plastics and fossil fuel oil industry has very intentionally put the blame for pollution on individuals.

This is an ad from the 1970s called the crying Indian ad. The message was, you can see that you can see it there. People start pollution. People can stop it. It was essentially this is your fault. Well, BP saw how successful this ad was in blaming plastic pollution on individuals instead of the companies that decided to produce the plastic.

And they did the same thing with the carbon footprint. So for years, I would give a presentation and someone would say, what car do you, what kind of car do you drive? And I’d say, this isn’t about me. This is a systemic thing. The fact that you’re asking me that means you’re trying, you’re, you’re playing into the hands of the fossil fuel industry, blaming me instead of a system that I did not create.

So, what I’m here to talk about is how we think about large scale change versus smaller level change. I came from this traditional, traditional corporate sustainability field, and one of the things you try to do is you try to reduce your carbon footprint. And we did. We spent years changing light bulbs, putting in building controls, building green buildings.

And our carbon footprint continued to go up. And I thought, wow, this isn’t what I was taught. We’re supposed to reduce our emissions and profit from it. And it’s all great. So I dug in trying to figure out what was going on. And it took me many days to realize that the utility where we get our electricity was primarily coal fired and had doubled down on coal so that the carbon intensity had increased.

And that’s why our carbon footprint had increased. So again, another epiphany, which was if we want to change the world in a way that will solve climate and if we want to reduce our carbon footprint, it’s not about us. It’s about changing the system. And in this case, the system was the utility which bought power from coal plants in and around Denver and Pueblo, Colorado.

So we spent, this is a long story that I’m going to make very short. We spent 15 years community organizing, finding candidates for this cooperative utility, which had public elections. And if you were a member, you could run and we won some elections and we lost some elections and we supported people like Lynn and Megan, some of the first women to ever be on this board.

And we daylighted the elections in the paper and we advocated and we campaigned and we knocked on doors and we got in trouble for it and we got yelled at and we got nasty letters written in the, in the papers and eventually we won. And this utility is now 80 percent renewable energy, which of course dropped our carbon footprint.

Enormously. And also the 50, 000 other customers in the region, and they’re continuing toward a hundred percent. So it’s a great example of how to think systemically instead of individually, and this is maybe the greatest thing we’ve ever done because the theory can be so broadly applied. I want to give you a few other examples of campaigns we’ve been involved with.

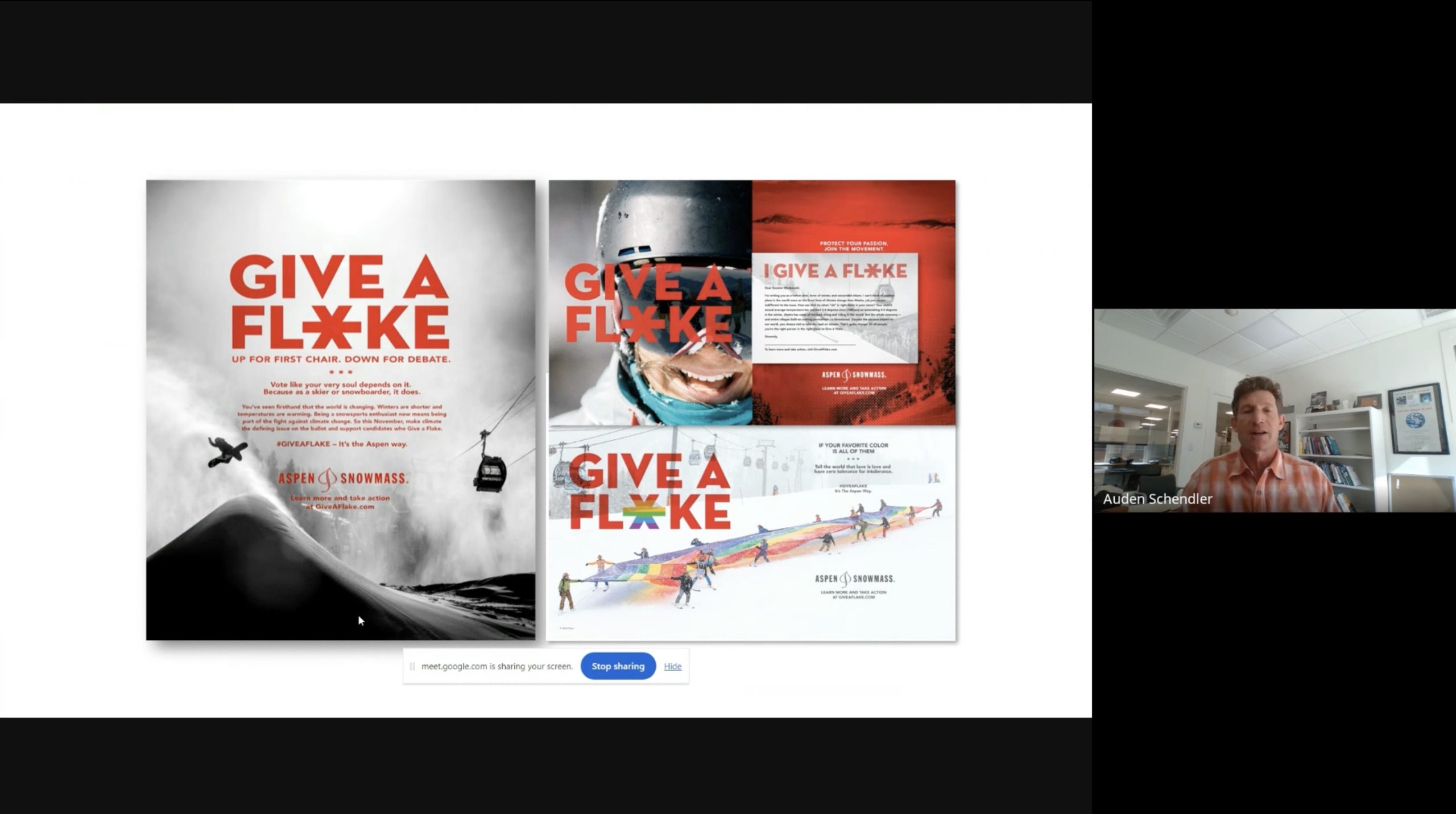

So in America, at least, and I bet this is true, um, throughout the world, people who had elected officials who had not who have taken terrible positions on climate, like climate science denial or complete inaction. There’s never a political consequence for that. And we said we’re going to create a consequence.

So we we created a campaign called Give a Flake, where we published in magazines, hundreds of thousands of prepaid postcards that you could rip out and send to swing senators who might vote one way or another. And when we did this, one of the senators from Alaska named Lisa Murkowski. Literally, the day the campaign went live, she freaked out and call her office called our CEO and said, what are you guys doing?

And we said, you need to do more on climate. And this was one of the first examples of an elected official feeling pain for a regressive position on climate. So we continued thinking like this. That’s Lisa Murkowski. We got in a fight with her in Outside Magazine, a back and forth. And the point is that was a success because now elected officials in the United States for sure they know they’re going to get in trouble if they have a regressive position on climate.

So in the United States, I’m sure, uh, uh, New Zealanders know there’s an organization called the National Rifle Association. That’s part of the reason we have so many school shootings is that this organization is very, very powerful. In fact, it won its issue at the Supreme Court. So, um, if you dig in on National Rifle Association, though, you see that at its peak, it was about 5 million members.

And yet, and it had a good amount of money, but money wasn’t the issue. It had very motivated people. And so a question we started asking was how big is the outdoor industry? Well, it’s anywhere from 40 to a hundred million strong. How come the outdoor industry in the United States? Or the tourism industry globally hasn’t really wielded political power.

And what if it did? What if you got this organ, these, these entities to care and to go to Washington, which is a picture here of protect our winters, which is trying to do this work in Washington. What if they did that? Couldn’t we have enormous power and couldn’t we drive political and policy change?

Certainly in the United States and probably globally. So that’s why we participated. We served on the board of protect our winters for a decade and they are doing this work from the outdoor industry. You could do this from the tourism industry too. It’s just pure advocacy and saying our job is to use voice and to wield power.

When you do it, this is a congressman from Florida named Ted, Ted Deutsch with some of the best skiers in the world. Um, Hadley Hammer and Angel Collinson. It’s fun because you’re engaged in a project greater than yourself. You’re doing good work. You’re trying hard. This is what humans were designed to do.

So this is not dismal. This is fun. It’s incredibly exciting. Now I’m going to give you some more regional examples of how solutions can be models for the world. And I’m going to run through these pretty quickly. So this is the Roaring Fort Valley near Aspen, where we live. And this is my company, Aspen One’s, uh, employee housing building.

This building is entirely electric, so that means that as our utility’s power gets cleaner, again, we were part of that, the building gets cleaner. So when this build, when the utility is 100 percent renewable, this building will be net zero. The roof is covered with solar panels, and it’s adjacent to the highway, so people can use mass transit.

This means people can work, live closer to where they work, commute less, not have to drive from long distances. And it’s a green building. This is a climate solution. It involves urban, urban planning, density in the core of communities and electrification. So we do this, but then we push it out to all our guests.

We have, you know, a million, 1.7 skier visits in our valley every year. Each of those people is a touch point that we can reach with a message. And we do that. And the tourism industry is perfectly positioned to do that kind of outreach. And people who are touring around the world are often disproportionately influential, tend to have a little more money and can drive change.

So then we said, where else can we reach our guests with just this kind of message? And one answer was we have maps on our chairlifts and we can put ads there. So this is amazing because you have a captive audience and this is one of our first ads. You can’t quite see it, but it was a graph of climate.

C02 and warming tracking and an ad basically for protect our winters asking people to join. But we were started this year. This is a new ad that will come out this winter, basically calling out the environmental movement and saying we’ve got to do more. The message here is essentially the same message I’ve just delivered to you.

We published this um, last year and we got a, we got an angry call from a CEO of a major fortune 500 company who was pissed off that we were calling out sustainable business as bunk. And I went to our CEO and I was like, Ooh, that was bad. And he said, who cares? That’s what we’re trying to do. So that’s exciting that we can mobilize behind us.

And when we get flack, we’re still supported. I talked to you about this idea of complicity versus real change. We’re going to have this ad also this winter on our chair. You can do this too. It’s just a question of venue. Is it in hotel rooms? Is it in lobbies? Um, this was one of our early ads where we partnered with the Yale Center on Climate Communications, and they said, use Pope Francis.

He’s widely respected. And so use a quote from him on climate and reach your guests that way. The opportunities are infinite, and this is incredibly fun stuff. So this year we’re going to be rolling out in the United States. Some of you may be familiar with our, our, um, uh, political situation and it actually is an essential climate situation for us.

It’s existential. And if, if Trump wins being blunt here, uh, we’re not going to be able to lead on climate and there are other problems with our democracy. So we’re running a social media campaign that doesn’t say how to vote. But it says, Hey, we respect you. If you’re on the fence, would you please consider climate in your vote in the presidential election?

Most Americans understand what that means. And then the Murkowski campaign where we had prepaid postcards for senators. We started rolling that out in hotel lobbies and ticket office locations. And here’s someone writing a note to Murkowski, adding a little personal touch and sending it off. None of this political pressure existed until the last five years in the United States.

Other interesting approaches we’ve had just running through them. We funded a study to show what the cost of climate change was in North America. The study, it cost us 6,000 to fund. It’s real science. And it was covered in the AP, which goes all over the United States, even all over the world. So think about that.

What is your marketing and PR department pay for a hit like this? 6,000? No, it’s more like 100,000 or more. Plus it’s changing social norms. People are understanding, oh, the thing I love is threatened by climate change. And then all of you in your industry have the opportunity to convene. This is a small room at the Aspen Limelight Hotel.

And we brought in Bill McKibben, maybe the leading environmentalist in the world. We broke the fire code. Look at this. It’s incredible. We people were outside who couldn’t actually get in the room. These are all skiers and visitors to our community who have some level of influence. This is actually a meeting we had with just a climate scientist and it blew them away last year.

We had the world’s leading expert on fossil fuel subsidies, which you’ve got to think is the most boring presentation possible and no one will come to it. In this case, the room was similarly packed. It’s amazing. And this is a giant opportunity, which is to convene and get people to understand what’s going on.

So. When just to pause and say, what is Aspen? One strategy it’s to wield power. Like I just described it’s to model solutions like the, the employee housing building, and then spread that word it’s to then use the media to amplify that message and get it out to the world, partly what I’m doing here is that, and it’s to convene like this picture and drive change and change social norms and national conversations.

There’s a longer story. I won’t go into. But we, we decided we’d boycott, uh, Kimberly Clark tissue to, uh, to protest the company’s use of endangered forest to make tissue, which doesn’t make any sense. 700 other companies joined that fight. And Kimberly Clark ended up after three years changing how it’s sourced fiber.

That’s crazy because what we are is a teeny ski resort without much political influence. And yet we’re able with others to force a large multinational to change on an issue critical to climate. You can think of this as asymmetric warfare. We ought not have the power to take on a larger opponent like that.

But we want, and then another weird thing we did is, is I got appointed to a regulatory body in Colorado called the air quality control commission. You can see me partly obscured on the right there, but this is boring stuff. It’s policy making, but I was paid. As an employee of Aspen one to make climate policy in Colorado.

And during that time, and I’m not taking credit for this, this was the group. We passed the strictest regulations on methane in the United States. Methane is a super greenhouse gas. We passed HFC regulations, which protect the ozone layer. And we passed radical clean car standards and zero emission car standards.

So there’s all this opportunity. You can put your, you know, the logo of a nonprofit you want to promote on ski uniforms. You can put the nonprofit you’re trying to promote on beer bottles so that when people are getting slightly buzzed and less inhibited, they click on a link that takes them to a phone number and they can write their elected official or Senator.

This is one of the better campaigns we did. Um, we can put climate change messaging at the top of Aspen Mountain. This is a melting gondola. People look at it, say what’s going on. And there’s a link to protect our winters, which can help you become a climate activist. So I’m going to conclude here by saying one response to the climate crisis is terror and just basically saying this is too much for me.

I give up. I’m gonna get in the closet, order Chinese food, drink whiskey and check out. But I submit to you there’s an opportunity here. And one of the problems is we think of ourselves as just normal people. You know, you’re being asked essentially to save civilization and your response could be I’m not that guy.

You know, I barely I barely even know where my car keys are. I can hardly get my kids out of the house. I can’t even sleep at night. I wake up to pee three times and I’m not Jackie Robinson. I’m not Gandhi or Rosa Parks or FDR. And what I’d say to that is that history is replete with people, uh, examples of citizens who have no power at all and drove disproportionate change.

This is Mohammed Bouazizi, the Tunisian vegetable vendor who set himself on fire in protest of how he was treated by the authorities, how he was treated. And I’m not saying this was a great tragedy, but Bouazizi started the Arab Spring. We don’t know how that’s going to play out. And, and, and he, he drove disproportionate asymmetric change.

I’m not saying set yourself on fire. I am saying you should be on fire for this issue. And it should dominate your thinking on a daily basis. You should see it as part of your mission in leading a life of meaning because there’s hardly anything out there more profoundly important than solving this problem.

I’m going to close with this, uh, painting, uh, of Raphael’s about the Genesis story of lots exile from the burning cities on the plane. If you don’t know this story, God got angry at the sinners in this town, and he sent an angel down, uh, to tell a lot. You’re my friend. Get out. And just one thing as you’re escaping before I burn it down.

Don’t look back. Okay, well, as the story goes, uh, lots wife look back and in punishment, she was turned into a pillar of salt. The American writer Kurt Vonnegut who was a great humanist. He said about that story, he said, so lots wife turned back and she was turned into a pillar of salt. But that’s why I love her.

I love her because what she did was so human. She turned around and looked back at the place her children grew up, where she got married, where she had her first kiss, where her children went to high school. And of course, you look back, it’s the most human thing in the world to do. And I submit to you that if you’re presented you the people I’m talking to right now with an opportunity to be part of a climate solution, and in doing that, you get to endow your life with some of the oldest ideas in human history, the most, the greatest aspirations living a life of dignity, of grace, of honor, and of tolerance, I submit that we can’t help but do it as people.

This is my last slide. This is a Mary Oliver American poet quote and my daughter Willow when she was little, but I think it’s a good question. What do you want to do in your life? You want to go to the office and come home and call it good? Or do you want to be part of something great? I’ve written up these ideas into a book called Terrible Beauty, which is available.

It’s going to be available in the United States in November, it’ll be available about three months later in New Zealand. And if these ideas interest you, um, this is much more and much more detail on how to think about this problem of complicity and how to move forward. So I’m going to stop there and Rodney and I are going to have a conversation.

Rodney Payne: One of the hundred or more interviews that I’ve done in the last year, I don’t think there’s anyone who’s transformed my thinking as quickly as you. It was a two hour conversation on the side of the ski field that totally flipped on its head, how I’d been thinking about sustainability. And I really appreciate you sharing that.

And even more so make sure to give a really big plug for your thinking as it’s captured in the book. And for anyone who can support Auden by pre ordering it, it is massively helpful for him. One description of your new book calls it a unique and essential roadmap for a new environmentalism. Now, everything you’re talking about, you’re coming at it from a context of the VP of Sustainability of a massive tourism business.

How do you, within that organization, find support and galvanize that sort of foundation that allows you to do what you’re doing from within your day to day role? Because I think for a lot of people that, that might be a, feel like a big barrier.

Auden Schendler: Yeah. And remember, first, let me say that. I think my ideas are pretty good, but most people don’t, you know, like, uh, I’m not desired by the corporate world for consulting because it’s so out there.

So I do need to thank you for, for kind of understanding what I’m talking about and appreciating it. And that’s why I’m here is I want to support you because you’re trying to do something different. Okay. So we’ve been doing this for almost 30 years. So we put in place this sort of momentum where it would be very difficult for our corporation to say, we’re all done with this.

Um, and in fact, we sort of, uh, have this, uh, treadmill where we have to keep going and do more and more for a given corporation, to me, the case for leading and leading in a non token way is profound. So what’s a token tourism approach? It would be. Don’t wash my towels, right? That, that saves hotels money anyway.

And is it not an environmental measure? It’s all, everyone does it. So leading beyond that is how you develop brand differentiation. You get pre you get perceived as progressive by your guests. They develop a loyalty. Um, there’s customer loyalty associated with this, but there’s also employee loyalty. And in our business, it’s very hard to attract really high quality people into the guest service sector.

We hear all the time. We’re so we’re here because of what you do. Um, so for, for, for many years have been a lot of different kind of analog cases for sustainability, including saving money, which you do do. But my argument is, your guests want to be part of something bigger. And if it’s, you know, you know, a shoe they’re buying.

They want it to be from a more responsible company, but if it’s an experience that’s imbued with meaning, that is a business proposition. So you get that, you build it and then you lock it in and it’s hard to reverse.

Rodney Payne: I still recall your answer to my question about how you see sustainability and when you talk about sustainability, you talk about it with climate fundamentally interwoven there, and you said, you know, it’s about being in business forever.

Can you unpackage that a little bit? Because I think that that also strengthens the argument around taking a stance within your organization and safeguarding the ability to recruit employees as they grow more concerned and the ability to attract customers.

Auden Schendler: Yeah, well, let me tell you a story. We were, we had remodeled our hotel in Aspen, the little Nell, and we were trying to open it for opening day.

And if we didn’t open it, as everyone in the room knows, you lose money. And I said, are we opening it? They said, no. I said, why? They said, the furniture hasn’t arrived. Where’s the furniture? Well, it’s stuck on the east coast and there’s a hurricane. So climate change has direct supply chain impact on our business.

So we started thinking about this idea of what, what actually is sustainability. And, and I, I came up with the notion that. It’s being in business forever and it doesn’t matter what your business is. So if it’s running a hotel, there’s a certain suite of things you have to do to stay in business forever.

If it’s being a parent, if it’s being a teacher, if you’re a shoe salesman, you have to look through all the things you need. So what do you need in the tourism industry? Well, you need stable government. You need a stable climate. You need the environment to be protected. You need to treat people well. You need to, uh, be able to insure people.

They need health care. So, so climate is sort of, we see as the uber issue on top of a suite of things you would have to address. If you actually want it to stay in business forever.

Rodney Payne: Systems change by definition can’t be done alone. And you mentioned one example of galvanizing bottom up support to transform your local utility, which is, you know, here I move.

What advice do you have to other businesses or tourism board, uh, executives who may have outsized influence in, in the places or place they operate? Around sort of stepping into that space to really drive meaningful action on climate.

Auden Schendler: Yeah, I mean, I think that their, uh, their involvement is is not necessarily unwelcome and communities do want leadership from bigger businesses in pot in ways that are positive for the community.

So, um, I think, you know, per the kind of outdoor industry, not actually doing this. If you look at the power of trade associations, trade groups, tourism groups, or even just a big entity, a hotel or, um, tourist organization in a city. They never wield any kind of political power. And if they do, it’s usually negative.

It’s like stop that regulation or don’t tax us more, but there’s this positive opportunity within these communities and the, and, and the, the benefits are. Direct to the company and the consumer but also to the brand twice a year aspen one puts out its sustainability report and Uh, you put it in many hotel rooms for people to raid uh when they’re visiting your properties as guests and You’ve also written, you know or talked to me about you know, not not every You’re not an environmental organization until your CEO has put out an op ed.

Rodney Payne: Can, can you talk a little bit about that, that specific opportunity for us to, to educate and, and, you know, address some of your strategies around having a stance and teaching visitors and, and what you think the potential is within the travel sector?

Auden Schendler: Yeah, well, so just to correct that we produce a sustainability report every two years, twice a year would be something else.

I’d be only doing that. But here’s an example of the power of that. I was at the gym and I met a guy who’s a property manager and I gave him my sustainability report. Thank you. A week later, he comes back and he said, how many of those do you have? And I said, a lot. He said, I manage 150 units in Aspen. So these are probably, you know, wealthy people.

Can I have some, and I’ll put them in all the rooms. Talk about a brand win. Can you imagine this is like people wearing Patagonia hats where your logo they’re just wearing because they like the company. So the point about, uh, you’re not a green company until your CEO has written an op ed about the need for action on climate is the gap between tokenism, recycling towels, uh, light bulb, changing green buildings, and doing something hard and dangerous and difficult that might actually drive change and companies that use their CEO’s power and voice.

Thanks. To drive that kind of change are the leadership we need. And then there’s many different ways to wield that power. It’s not just your CEO.

Rodney Payne: By the nature of this topic, I’m going to guess that a lot of our viewers will be younger. And I’m wondering if you could restart your career, knowing what you know now.

What would you do differently or what advice would you have for your younger self?

Auden Schendler: Yeah, you know, I, I kind of bought the thesis hook, line, and sinker that business could solve climate change at a profit without regulatory intervention. This is sort of the free market vision that has been pervasive and a pervasive failure in the world.

So I guess I would have wanted to be more. Um, even though I’ve always been ornery and questioning and uncooperative, I would have been more that way. And the question I asked eventually was, is what we’re doing And so if I’d started that questioning earlier, I think I would have been able to make more progress.

Rodney Payne: And what advice do you have to other people in your shoes with a sustainability, you know, leadership job title around. Perhaps leapfrogging, um, some of the, the incremental things that we’re sort of asked to do and starting to shift into the things that really move the dial.

Auden Schendler: Yeah. So people in my field are typically typically in charge of operations.

And so that means the way you’re defining sustainability or climate solutions is in terms of carbon reduction, green buildings, more efficiency on your property, renewable energy. And what I submit is that shouldn’t be called sustainability. It should be called business management because it typically saves money.

It’s good for your brand. It just makes a lot of sense. Instead, sustainability takes place in the government affairs department. And so you need to knock on that door or get in that department and say, Hey, what we really need to bolster our operational work, which gives us credibility is to have you advocating at a greater level for some important issues.

It doesn’t have to be climate, but that’s the primary issue. But there’s a whole suite of other things. Um, that affect business and that business could be involved with. So sustainability, the department of sustainability really is government affairs.

Rodney Payne: Is there anything you’d like to leave us with, uh, in, in terms of the potential within the global travel industry and the moment that we’re in?

Auden Schendler: Yeah, I mean, I’d say all, all of, of you are probably looking at the climate crisis and feeling a little panic and a threat to business. And I would say. This is the greatest opportunity that humans have ever had. We have a chance to effectively save civilization. And the tourism industry is one of the most powerful because people love you and you are the thing that they love in the world.

And so the thesis of my book is we can use that, the things we love as a, as a propulsion, as power for solving the problem, the threat to all of those things. So it’s the greatest opportunity ever presented to civilization.

Rodney Payne: Thank you and thanks for everyone to joining today for part of the 24 Hours of Innovation event on World Tourism Day presented by Destination Think.

Again, I encourage you to find Auden’s book. It’s available on Amazon now, right Auden?

Auden Schendler: Yeah, it can be pre ordered and it’ll will get it overseas in about five months.

Rodney Payne: And you can find many more inspiring speakers on our website at DestinationThink.com. If you’d like to hear more from Auden, you can also find, uh, an in depth interview with him on the travel beyond podcast, and please do check out his new book, terrible beauty, which, uh, as Auden mentioned is coming out in November, we want to make sure that we see ideas and solutions spread around the world.

We think that that’s the power of travel. And if you enjoyed this presentation, please make sure to share it. Thank you very much for joining. Thank you.

David Archer: This has been Travel Beyond presented by Destination Think, and you just heard from Auden Schendler, Rodney Payne, and Hadley Dryden. For more resources and show notes, visit our website at DestinationThink.com. This episode was produced and has theme music composed by me, David Archer, Sarah Raymond de Booy, my co producer, Lindsay Payne, Jamie Sterling, and Cory Price, as always, provided excellent production support.

And if you 5 star rating to help more people find our show. Thanks so much for listening and we’ll catch you in the new year.

0 Comments